After the Hunt reveals the truth through its interior design

The psychological cancel-culture drama After the Hunt sees Luca Guadagnino turn his attention to academia — a world built as much on reputation and performance as on intellect. The film follows philosophy professor Alma Himoff (Julia Roberts), whose carefully managed life begins to come apart when a star student (Ayo Edebiri) levels an accusation against a colleague (Andrew Garfield), and a long-buried truth of her own moves dangerously close to the surface.

Written by Nora Garrett, the story is set against the polished backdrop of Yale: a place where architecture itself conveys order, legacy and institutional certainty. Guadagnino has often treated interiors as emotional cartography, but here the rooms become moral architecture — sculpted, composed, and quietly revealing.

Working once again with production designer Stefano Baisi (who also designed Guadagnino’s Queer), the two create not only Yale’s classrooms and corridors, but the domestic interiors where Alma rehearses, polishes and presents herself. Yale is the stage; the interiors are the performance. Her two apartments tell us what Alma will not yet say. They reveal the truth long before the dialogue does.

A Manhattan state of mind

Alma and Frederik’s home is not politely tasteful minimalism — it is character made architectural. Modelled on a ‘Classic Seven’ layout more commonly found in New York’s grand Upper West Side buildings such as The Dakota or The Langham, it signals a particular cultural lineage: the world of the American intellectual elite, steeped in books, history and inherited taste. The geography may be New Haven, but the psychology is Manhattan — legacy, curation and a life lived through ideas as much as things.

The design also places the film within a familiar cinematic tradition: the New York intellectual apartment as autobiography. You can trace its ancestry through Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters, later echoed in The Squid and the Whale, and more recently in Maestro and Park Avenue. These are rooms that behave like confessionals — where books and textiles speak before the characters do.

We the audience respond to these spaces because they feel inhabited rather than styled; culture is soaked into the grain of the furniture.

Inside Alma’s apartment in After the Hunt: A home built in layers

Baisi conceived the apartment as though it had passed through several hands: “We imagined three distinct layers of time,” he says. “The grandparents were European émigrés bringing the vocabulary of the Wiener Werkstätte and Bauhaus [most visible in the cool, early modernist rigour of the kitchen]; Frederik’s parents lived through the Kennedy domestic era of warmth and refinement [mirrored in William Morris floral upholstered sofas]; and Alma and Frederik add their own layer — reupholstered furniture, artworks from travel and a more intellectual sharpness that feels personal but controlled.” We also notice a selection of modernist furniture classics.

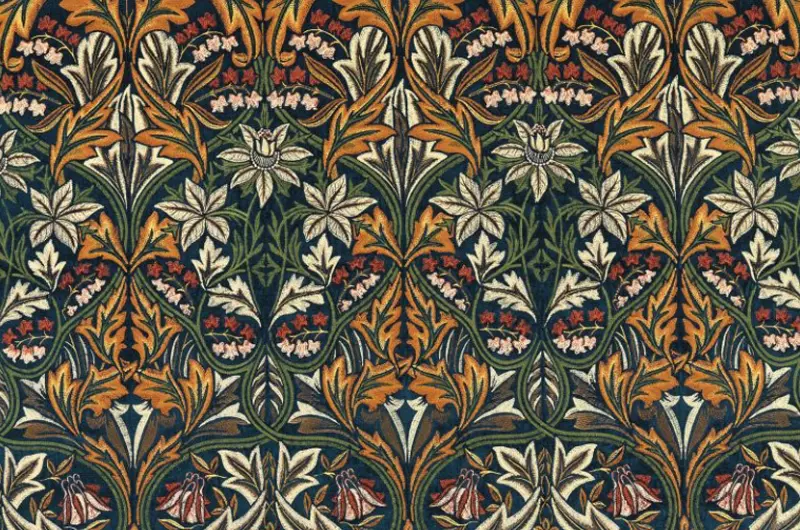

The apartment is laid out as a series of enfilade rooms allowing the story to shift tone without ever leaving the domestic world. One living area with red walls, deep orange-tobacco velvet sofas and a gold and glass coffee table feels warmer and denser than the others, punctuated by a green Flowerpot table lamp by Verner Panton. The palette shifts gently in the adjoining space, where a pair of floral sofas upholstered in Morris & Co’s Bluebell Embroidery Fabric speak to that Kennedy-era layer of cultured ease.

The dining room pivots around a Josef Hoffmann table Baisi found during a visit to the historic Viennese glassware company Lobmeyr — serious, sculptural and softened by white-framed chairs with red-and-white checked textile details, a domestic note that turns the piece from museum object into heirloom.

In Frederick’s study, a beautifully striped sofa (from Luca Guadagnino’s private collection) shares space with Josef Albers paintings and an Eileen Gray E1027 side table, modernism distilled into glass and a single chromed gesture — small, perfect, and quietly confident.

African and Haitian sculptures add a cosmopolitan layer and were chosen to suggest travel, worldview and cultural capital. “They belong to the layer of Alma and Frederik’s life, representing objects collected through travel and experience. They’re not displayed as trophies or decoration, but as subtle traces of a couple who have lived, read, and seen the world — a cultured accumulation rather than an aesthetic statement,” says Baisi.

Even the bathroom participates in the choreography: during a moment when Alma is physically unravelling (vomiting down the toilet), the floor tiles remain cool and elegant — the house holding its poise even as she loses hers. Beauty here is containment.

The bedroom continues this measured restraint. A Guglielmo Ulrich bed provides a clean architectural centrepiece — Milanese in spirit, elegant without ornament. Textile wall hangings nod gently to Bauhaus weaving, softening the austerity into something contemplative. These are reproductions of Anni Albers’ Black White Gray (1927/1964) and Ancient Writing (1936), chosen to add warmth and texture without introducing figurative art. Baisi says the pairing balances the room’s horizontality — “two instead of one helped us find equilibrium, perhaps like Alma and Frederik themselves.” White bedside lamps glow like sculpture rather than decoration; set decorator Lee Sandales sourced them for their soft diffused light, where material presence mattered more than provenance.

Several furniture items come from Guadagnino’s own collection — including pieces by Gio Ponti and Piero Portaluppi — as well as a painting of a fish by Alvaro Barrington. “His paintings often explore migration, belonging, and how personal history survives through materials,” Baisi says. Placed in the apartment’s entrance, it becomes an unconscious metaphor for Alma and Frederik — two people navigating identity, intellect and instinct. Crucially, it is one of the few pieces Alma bought herself, a subtle marker of her cosmopolitan sensibility and quiet independence.

The space is exquisite, but it never fully relaxes. Nothing drifts. Nothing loosens. The outer world and the inner world are not the same. What Alma shows is not what Alma feels.

The second apartment: Where the mask slips

Alma’s second apartment arrives like a confession. Tucked in the gritty, industrial Wharf district, it is bare, uncurated and functional. It’s cool, but stripped back – the place she goes to think the thoughts she cannot risk showing elsewhere.

Baisi describes it simply: “By subtraction.” If the main apartment is layered, cultivated, thick with history, this one is psychological rather than social — “a mental space rather than a shared one,” he says.

Duality revealed

Once this duality is established — polished exterior versus unguarded interior — you start to see it echoed everywhere: in the black and white artworks, the choice of two separate textile hangings above the marital bed rather than one, in Alma’s black-and-white pyjamas, the stripes of the study sofa. Even a restaurant that appears to be a 1950s-style diner is revealed to be an Indian Tandoor — another interior wearing a costume. Surfaces tell one story while concealing another.

A close-up of a $20 bill featuring Andrew Jackson lands the same point quietly: Jackson fought against central banking and paper currency, which makes his face on U.S. money an elegant metaphor for principle turned into performance. One of the professors all but confirms this theme when he says they are “in the business of optics, not substance.”

Yale as a mirror

“It happened at Yale,” is the first line spoken in the film — a location-as-judgment, not just a setting. Yale doesn’t simply host the scandal; it legitimises it. The university functions like the apartment: ethics staged as image, culture performed through architecture.

Alma moves through this world with the same contained precision she maintains at home — composed, disciplined, curated. The Wharf flat is the only space in the film where she stops presenting and simply exists.

Although the story is set at the New Haven–based university, almost everything was built from scratch at Shepperton Studios in the UK, with a few brief exteriors filmed at Cambridge University. Baisi says the intention was “not literal geography but institutional psychology” — to build the idea of Yale, not a postcard replica of it. Yale becomes a structure of performance, not a backdrop: stone as certainty, heritage as armour.

When rooms have a voice

We often talk about beautiful interiors in cinema, but After the Hunt goes further: design precedes the characters. The rooms tell us who Alma is before she does. The audience may not identify the shift consciously, but we feel it: first the seduction of taste, then the quiet dawning that taste is also a holding structure.

The apartment lingers because it isn’t simply décor — it is narrative. In Guadagnino’s world, the rooms speak. The plot only confirms what the furniture has already told us.

After The Hunt is out now in cinemas.

This feature is FREE to Classic members.

Join our newsletter community to receive Film and Furniture inspiration direct to your inbox and we’ll UPGRADE you to Classic Membership (which includes access to our exciting giveaway draws) for FREE.

To access in-depth features, video interviews, invitations to pre-release film screenings, major exhibitions and more, become a Front Row or Backstage member today!