Set for Adventure: Guest feature on spy film set design by SpyVibe

Set For Adventure looks at conventions and styles in film set design of the Mystery/Adventure film genre and is one of SpyVibe‘s most popular features. SpyVibe founder Jason Whiton has kindly allowed us to share it with our avid Film and Furniture fans.

Pads and Lairs

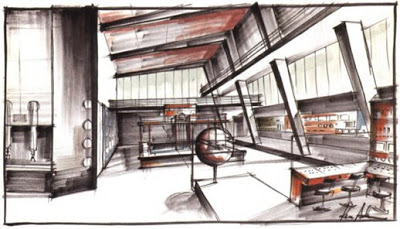

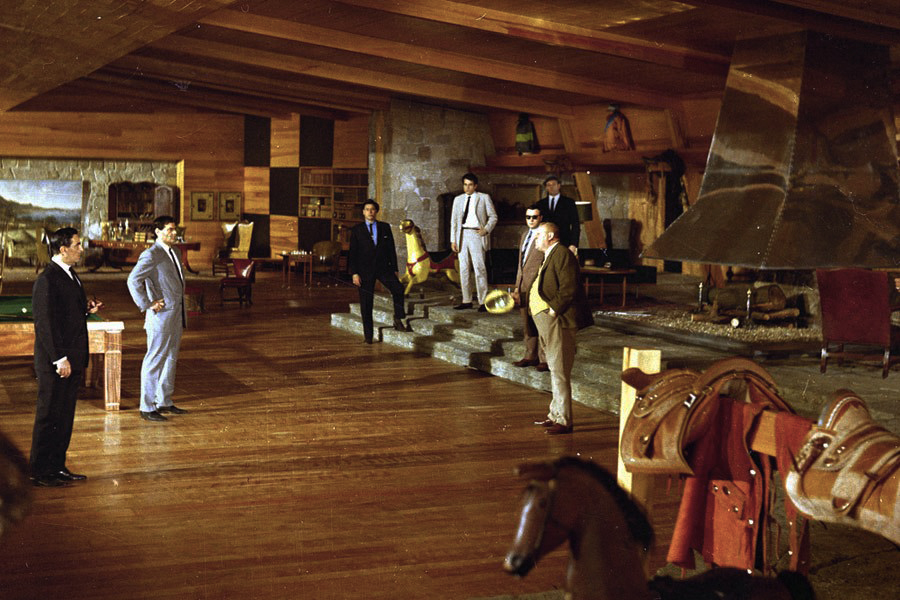

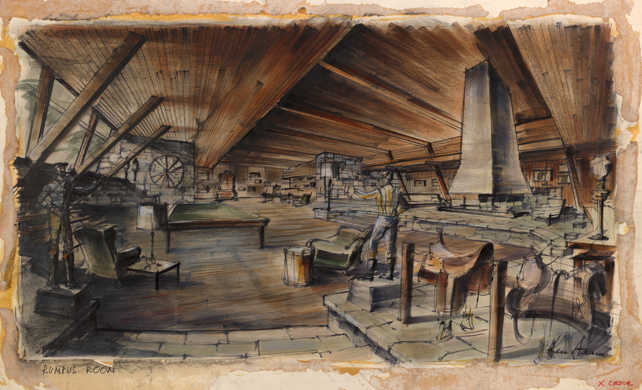

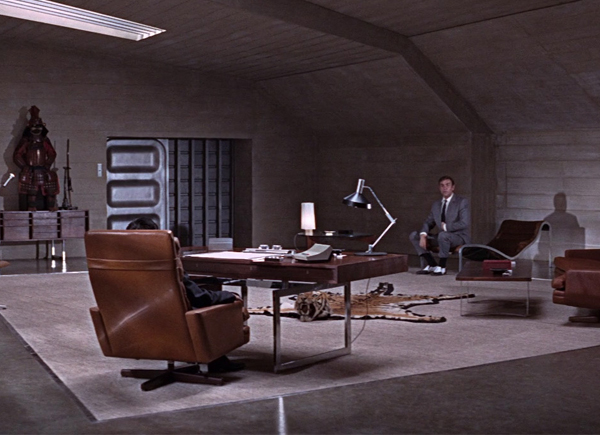

Creating your Secret Agent Pad or Evil Lair? Need a cavernous room with that ultra-modern Spy Vibe? Chances are that your wish-list has sprung from the mind of influential designer, Ken Adam (Dr. No, Goldfinger, Dr. Strangelove). Adam was left to design the first Bond sets for Dr. No (1962) while the crew was in Jamaica filming on location. Blending the expressionist aesthetic of his Berlin childhood, the modernism of his architectural studies, and Cold War technology, Adam created indelible sets worthy of the Space Age and launched the 007 image into public imagination. His rooms were vast and dynamic, with tilted, triangular ceilings and circular skylights. The synthesis of his cultural pallet, Dr. Caligari, Post-War lifestyle trends, paperback thrillers, and mid-century modern would inspire a look – a Spy Vibe style of architecture and design.

1930s-1940s Heroes

The idea of Pads and Secret Lairs really took flight with serialized adventures of the 1930s and 1940s. One of the most popular genres was the Mystery Detective story – sensational yarns about wealthy sleuths who battled incognito from Inner Sanctums against the fiendish plots of an array of masked villains with ever-colorful names. The largely male audience reveled in the exotic locations, and kids were hooked by the cliffhanger death traps that escalated with each chapter. Writers cooked up fantastic spaces with fun elements like trap doors, secret chambers, escape hatches, and deadly gadgets. Adventure was to be found everywhere, from Tarzan’s jungle to Flash Gordon’s rocket ship, from Zorro’s night raids to the world of wartime spies and saboteurs. The Spy Vibe films of the 1960s drew on this colorful tradition, which set the stories apart from other crime/detective movies.

1950s: Post-war Lifestyles

Cliffhanger Serials faded by the mid-1950s with the advent of television. Crime and horror comics soared briefly until censorship emasculated the industry with the creation of the Comics Code Authority in 1954. Fans with a taste for edgier entertainment could find excitement among men’s adventure magazines, paperback thrillers, and private eye heroes. It was in this cultural context that a forty-six year old journalist finally sat down to write the “spy story to end all spy stories.” Some say he wrote to stave off the anxiety of marriage. Three years later, American Popular Library released his first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, in paperback in the United States in 1955. Anthony Boucher of The New York Times dismissed it as “pretty much to the private-eye school” of fiction. Despite this review, the novel would eventually launch a film franchise that would prove to be a beacon of hope for guys living in the claustrophobia of 1950s suburbanization who chafed for a more masculine ideal, and who craved a freedom of lifestyle.

One particular boy who grew up in this climate dreamed of becoming a cartoonist, but found that his greater talents lay in his ability to envision a personal view and approach to living that, as it turned out, many men could relate to. That cartoonist was Hugh Hefner and his Playboy Magazine became a major influence in the 1950s and 1960s on men to entertain a way of life based on pleasure, curiosity, and a male aesthetic.

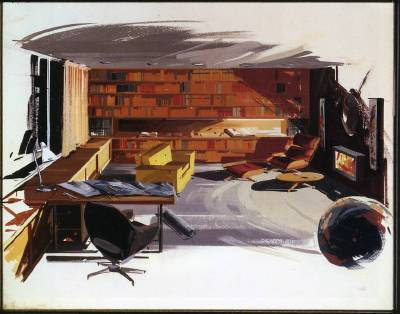

Features about architecture and interior design gained popularity quickly. The articles sported illustrations of ideal homes and modern pads that electrified the imaginations of men weary of caving to the nine-to-five paradigm of the grey flannel suit-set.

History professor Elizabeth Fraterrigo has written a study of the magazine’s influence: “In the 1950s and 1960s, Playboy promoted a decidedly masculine vision for the realms of home, work, and leisure in its textual and literal construction of their spatial corollaries – the bachelor pad, the white-collar office, and the realm of urban nightlife – which served as counterpoints to the cultural emphasis on the suburban-situated nuclear-family home. Through its magazine, television programs, and key-clubs, Playboy identified spaces where men could craft and nurture a masculine identity based on style, leisure, and consumption” (Elizabeth Fraterrigo/UNLV).

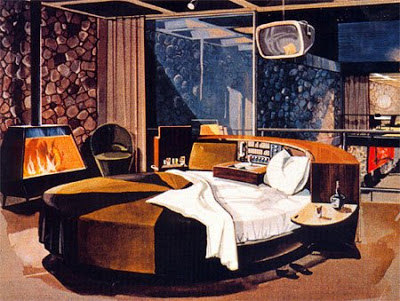

I imagine that the designers themselves had the simple, sweeping curves of the mid-century modern aesthetic in mind when they drafted their work during that period. But I agree with Fraterrigo that those archetypical bachelor pads with Hi-Fi Jazz, Scandinavian style, and cocktail lounges were, well… for bachelors. Or at the very least, for sophisticated young couples who embodied the urban, perhaps swinging, lifestyle.

By nature, the ultra-cool interiors symbolized freedom and individuality over the suburban family B.B.Q ideal that was prevalent in mainstream culture. A reaction was the lounge culture of kitschy LA ranch houses, Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack, and at a higher level, the era of Alexander Calder and Eero Saarinen.

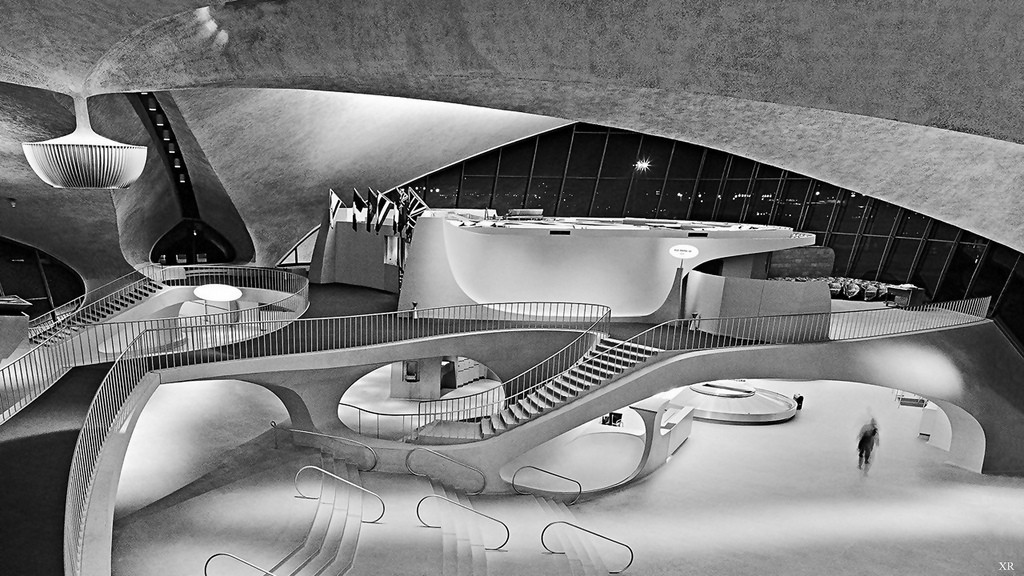

Production Designers keen to establish characters who embodied this individuality found inspiration among this wider, artistic world. Mid-century modern flagstone mixed with plastics, inflatable furniture, neo-classical antiques, and with the ever-advancing technology. Ken Adam’s film designs, which he called “slightly tongue-in-cheek, slightly ahead of contemporary,” became as culturally influential as Saarinen’s TWA terminal (1961).

1960s: Youth Culture for the Space Age

The fantastical movie sets of the 1960s were also a sign of an emerging youth culture – playful, lusty, rebellious, modern, and pushing a breakdown between consumer design and Fine Art.

This generation found its leader in John F. Kennedy, who launched us into the Space Age in May 1961. Three months earlier, JFK helped to build the popularity of James Bond by adding Ian Fleming’s From Russia With Love to his top-ten list of books for Life magazine. Producers were already working to bring Bond to the big screen, and Ken Adam was busy creating the sets that would establish Bond’s character in the larger-than-life world of rockets and of evil villains worthy of Kennedy’s era.

The British public was introduced to Adam’s visual style for 007 in an October 1962 premiere, followed by a US premiere in May 1963. It was the launch of a new look and feel for entertainment that embodied the times as much as Hefner’s Playboy and the arrival of The Beatles (UK/Jan 1963, US/Feb 1964).

Ken Adam went on to design many Bond films and now-famous sets, including one of the ultimate pads – Goldfinger’s transforming rumpus room. Other notable sets include Spectre HQ (Thunderball), the War Room (Dr. Strangelove), Blofeld’s volcano missile base (You Only Live Twice), and his Oscar-nominated Atlantis (The Spy Who Loved Me). Adam was also the visionary behind many iconic spy props, including the Aston Martin DB5 (Goldfinger) with its lethal accessories.

Repeated and parodied for forty years, Ken Adam’s mixture of expressionism, modern-minimal and high-tech gadgetry remains an irresistible cocktail and defines Spy Vibe design. With the growing baby-boomer generation buying movie tickets, designers that followed Adam added extra doses of grooviness, producing memorable sets for films like Danger Diabolik, Our Man Flint, and Barbarella. The sets elicit visions of Cold War culture – Playboy, the sexual revolution, the Space Race, and the merging of Fine Art and consumer culture. Where the bachelor pads of the Doris Day/Rock Hudson movies of the 1950s were left behind for marriage and domesticity at the end of the films, the Pads and Lairs of the 1960s spies endured as focus on the individual became more accepted. The hero of the 1960s could not be so easily tamed. Dr. No was killed, but another baddie would always emerge from under a new rock. “The End, but James Bond Will Return.”

Set For Adventure will appear in Jason Whiton’s upcoming book, SPY VIBE, about the 1960s Spy Boom and thriller genre (Hermes Press, January 2017).

The book Ken Adam Designs The Movies and films mentioned in this article are available from our store.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Instagram

Instagram Pinterest

Pinterest RSS

RSS