The Art Deco Nightmare of Batman (1989): How Gotham City Became a Character

When Tim Burton made Batman in 1989, he created a world—one that was impossible, dark and alone. Gotham City wasn’t just a location. It was a living, breathing monster of industry and decay, that would consume you whole.

Expert production designer Anton Furst built it out of steel, concrete and shadows, drawing from 1930s Art Deco, German Expressionism and the grime of post-war urban landscapes. The result was a city that was both ancient and futuristic. A city that could only exist nowhere else.

Gotham: A City Without Sun

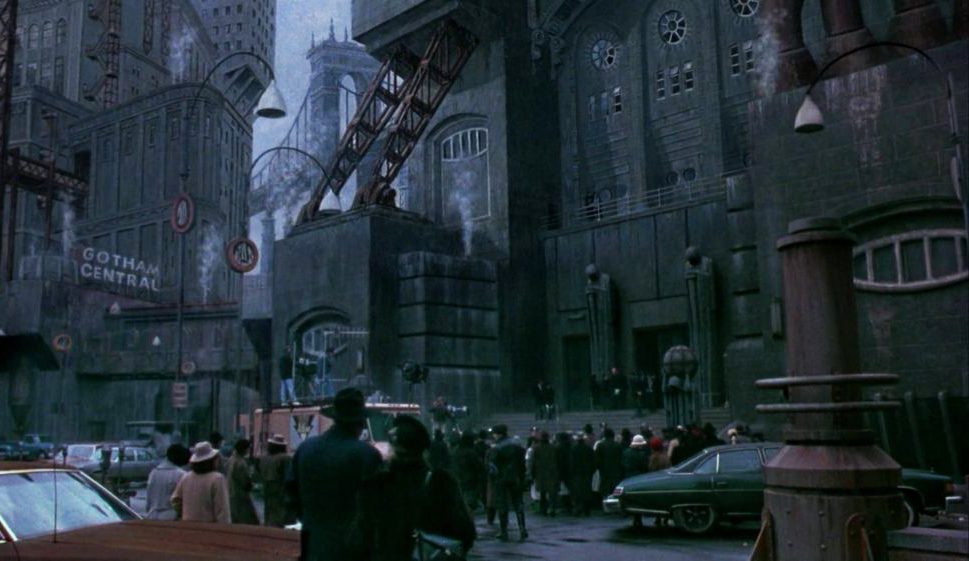

Furst’s Gotham wasn’t a real city. It wasn’t a dressed-up New York or a reworked Chicago. It was built from scratch, a Frankenstein of architectural horrors. He described it as if “hell had burst through the pavement and kept on growing”. It was an impossible city of twisting alleys, giant statues and brutalist skyscrapers that stretched into forever night.

The streets were clogged with industrial detritus. Steel girders loomed above like the bones of a long dead giant. Light never touched the ground. Instead steam rose from the manholes, neon flickered in the rain and shadows swallowed whole entire city blocks.

When they moved to Pinewood Studios, the team had to build a city from scratch. They needed an army of builders, top-notch furniture assembly services, and a vision that went beyond the boundaries of traditional set design. Piece by piece, they ended up creating a full-scale Gotham backlot, one of the largest ever built. An assembly service for horrors, a city of oppression and beauty, built with every furniture installer guided by the masterful Furst.

Gotham DNA: Art Deco, Dystopia, Decay

Gotham wasn’t just big. It was a city that had grown too big for itself, where every new building was slapped on top of something older, heavier and uglier. The Art Deco influence was everywhere—sweeping arches, iron filigree, impossibly tall doors. But beneath that elegance was rust, grime seeping in at the edges.

Burton and Furst drew heavily from Metropolis (1927), Fritz Lang’s city where the rich looked down from ivory towers and the working class toiled in the depths. You can see that in Gotham’s architecture—the soaring cathedrals, the oppressive skyscrapers, the way the city seems to be watching you.

The modern city was an influence too. Furst drew from 1980s New York, when Times Square was less a tourist trap and more a crime scene. Billboards flickered through cigarette smoke, alleys oozed grime and buildings loomed over the city like silent giants. Gotham took that and turned it up to 11.

A City That Moulds Its People

Every frame of Batman (1989) tells you something about the world before a single word is spoken. The city shapes the people who live in it. You don’t just live in Gotham—you endure it.

Batman, in his chiseled black suit, looks like he was born from its darkness. He’s a part of the city, a fixture of the night, blending into the buildings as easily as a gargoyle on a cathedral. The Batcave is a contrast— sleek, modern, clean. The only place in Gotham that’s not dirty.

Then there’s the Joker. Jack Nicholson’s clown prince of crime is a sore thumb—he’s a neon sign in a city of grayscale. His gaudy purples and green clash with the city’s dull, industrial tones. He doesn’t blend in. He pollutes. He walks into Gotham’s already broken aesthetic and makes it worse.

Vicki Vale, the outsider, doesn’t feel like she fits in. Her world is art galleries and globe-trotting photojournalism. She moves through Gotham like she’s visiting another planet. Because she is.

The Set Pieces That Are Iconic

Some sets become iconic the moment they appear on screen. Batman (1989) had a few.

Wayne Manor, a dark castle on the edge of sanity, with furniture that was more for show than for sitting. A home, but not a warm one. A place where Bruce Wayne lived but never felt at home.

Axis Chemicals, the industrial hellhole where Jack Napier fell into a vat of acid and emerged as the Joker, was a factory of horrors. Rusty catwalks. Bubbling green vats. A place where workers would get lost and never go home.

Gotham Cathedral, a towering monstrosity, was the final showdown. A Gothic hell of twisted stone where Batman and the Joker faced off in a place that felt older than time.

Each of these locations supported the story, the characters and the very soul of Gotham. They weren’t just sets. They were storytelling devices, bending the film in ways words couldn’t.

Furst’s Legacy

Furst won an Oscar for Batman and deserved it. His Gotham City defined Burton’s film and would shape how Gotham would be seen for years to come.

Batman: The Animated Series (1992) built upon his designs and made Gotham a 1940s noir city that never moved on. Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight trilogy went more realistic but still had Furst’s skyscrapers. Even Matt Reeves’ The Batman (2022) couldn’t get away from Batman (1989)—its wet streets, its perpetual night.

Sponsored post

This feature is FREE to Classic members.

Join our newsletter community to receive Film and Furniture inspiration direct to your inbox and we’ll UPGRADE you to Classic Membership (which includes access to our exciting giveaway draws) for FREE.

To access in-depth features, video interviews, invitations to pre-release film screenings, major exhibitions and more, become a Front Row or Backstage member today!