The film sets and furniture of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange: “A real horrorshow” Part 1

The main character Alex DeLarge is played brilliantly by Malcolm McDowell, Kubrick’s one and only choice for the part. He reportedly would not have made the film without McDowell’s participation. It was rumoured Mick Jagger had been mooted for the role before Kubrick was involved and whilst McDowell is just perfect as the antisocial delinquent, references to Mick Jagger crop up in the movie. Alex narrates most of the film in Nadsat, a fractured slang composed of Slavic (especially Russian), English and Cockney rhyming slang.

Having researched the architecture, furniture and film sets of the movie in more detail recently, I realise now why I find it so compelling and fascinating – and I have come to reconcile my conflicted thoughts.

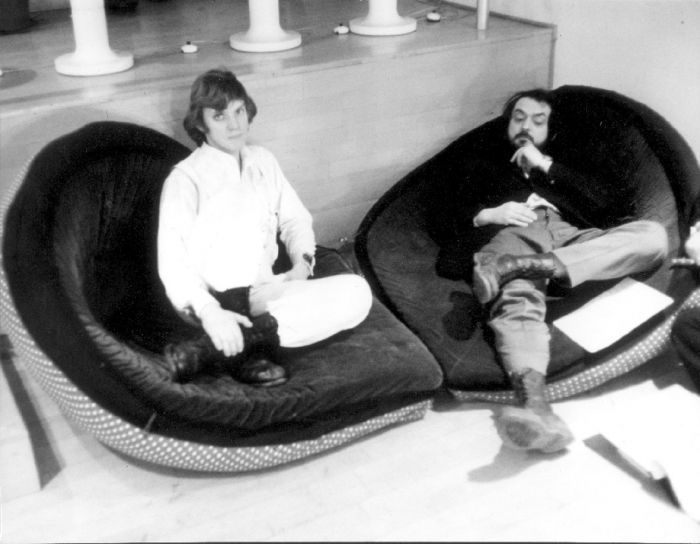

The majority of the movie was filmed within an hour or two of Kubrick’s then home in Barnet Lane, Elstree, Hertfordshire, England and the majority was filmed in real houses and apartments. Only two or three sets were designed and constructed within a film studio (Kubrick wanted to prove he could make a relatively low budget movie after the extravagance of 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968).

Production designer John Barry was an architect with experience in stage design and entered the film business as a draughtsman on the epic Elizabeth Taylor film Cleopatra in 1963. Later he became production designer on the Clint Eastwood action film Kelly’s Heroes in 1970. Barry was offered the job of designer by Kubrick for his never-completed film Napoleon but hired him again as production designer on A Clockwork Orange. George Lucas also hired him as production designer for Star Wars for which he received the Academy Award for Best Art Direction.

-

Hicks’ Hexagon officially licensed luxury rugs and runners, designed by David Hicks, as seen in The Shining Overlook Hotel

Designer: David Hicks

Directors: Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, Mike Flanagan

Shop NowOfficially licensed Hicks’ Hexagon rugs and runners as seen in The Shining‘s Overlook Hotel (original design by David Hicks). High quality, custom made, hand tufted 1 ply wool. One of the most iconic carpets in film

Approx £1,308.33 – £6,120.00 / $2056

The hyper-stylised film sets and furniture of A Clockwork Orange tell a story in their own right, acting as signifiers which portray a parallel narrative. I realise in my digging that, coincidentally, many of the pieces touch upon many of my personal interests: From mid century and retro-futuristic interior design and space age furniture, to Pop artists such as Allen Jones, Herman Makkink, Cornelious Makkink and to record sleeve/product designer Roger Dean. All sit together to create an unsettling atmosphere and combine the fantastic with the obscene.

What makes it all the more disturbing is the set design and locations are recognisable enough to tell us the film is set in the near future – not so far away that it feels beyond our own realm, but a future just around the corner. Together with the costumes by Milena Canonero and the electrified, classical score by Walter (later Wendy) Carlos, the production design tells us this is a reimagining of what the present might be – should we not heed the themes of the story.

Kubrick and Barry would have worked very closely to achieve a look and feel which assaults the senses and is another example of how Kubrick uses a characters surroundings to echo their inner world. The film examines the nature of free will, of good and evil, of (almost cartoon) violence and throws it all in our face with velocity – starting with the opening title sequence of bright, brash full screen colours and the first scene of the Korova Milk Bar (one of the few constructed sets). Viddy well.

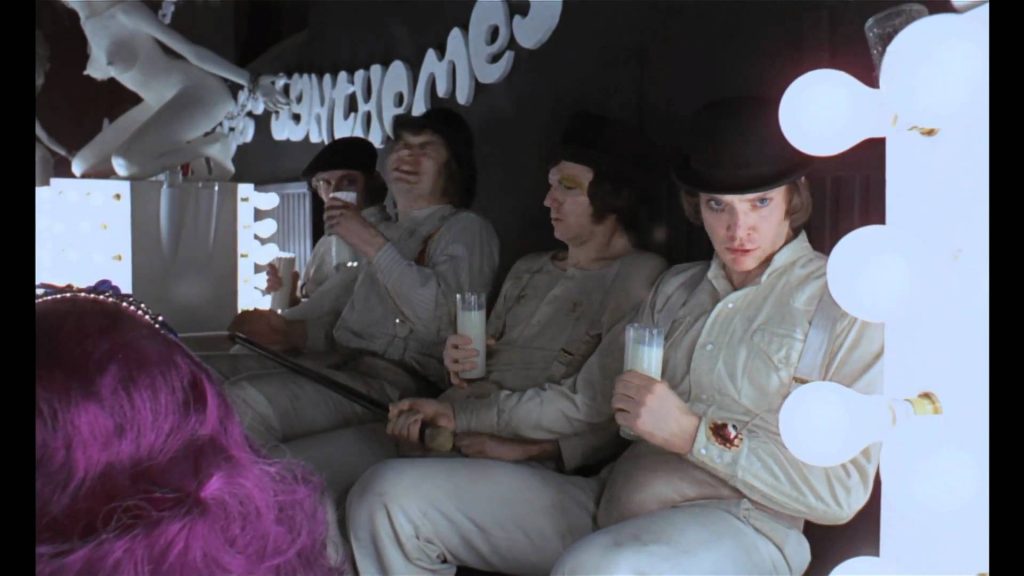

The Korova Milk bar

This opening scene begins close up on Alex, then pulls out to reveal a film set which alarms and shocks from the get go. John Barry had seen a sculpture exhibition where female figures were displayed as furniture. We know this now to have been the exhibition of Allen Jones whose first erotic chair sculpture was in 1969 and his first group of fibreglass figure sculptures including Hatstand, Table and Chair gained international attention when exhibited in 1970. Jones turned Kubrick down in his request to use them in A Clockwork Orange but the concept was carried over into creating fibreglass nude figures created by Liz Moore.

As an aside (but an aside which further cements my connection to A Clockwork Orange), Allen Jones’ muse was my first boss – his wife and design consultant Diedre Morrow – who wears her hair in a distinctive bob as do most of Jones’ sculptures. As a young graphic designer I would from time to time do her food shopping in the local supermarket.

The window-less Korova bar is separated from the outside world with black walls and the white fibre glass nudes, the only colour is created by their brightly coloured wigs and pubic hair. It is instantly confrontational. Alex’s gang of Droogs (‘Droog’ from the Russian word buddy) rest their drinks on them as tables and pour cocktails (drug-laced milk called ‘Moloko Plus’) from their breasts which “would sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of the old ultra-violence”.

People as furniture is perhaps the ultimate objectification of women and underlines Alex and his Droogs disregard and menace. As a feminist, this should go against all my principles but on an aesthetic level I also love Allen Jones’ pop art. The author of Idyllopuspress.com Juli Kearns points out “People as furniture were already spoken of in Lolita and Peter Sellers himself materialised out of a chair covered with a white cloth… and also in Eyes Wide Shut with a man acting as a table at Somerton. One could say it is a kind of shape-shifting, which we also have referenced with the red Djinn furnishings in 2001, Djinn being shape-shifters and the red chairs were actually “Djinn” chairs by Olivier Mourgue. So, the mannequins are more than mere decoration, they are an idea used throughout Kubrick’s films, appearing first in Killer’s Kiss in the mannequin storehouse in which the boxer kills the owner of the dance club”.

A similar ‘milk-bar maiden’ was re-created for a video by rock artist Rob Zombie a few years back, and this pop princess was created for the video (below). It was sold through 1st Dibs.

Kubrick himself stated that “… modern art’s almost total pre-occupation with subjectivism has led to anarchy and… the notion that reality exists only in the artist’s mind, and that the thing which simpler souls had for so long believed to be reality, is only an illusion…” (ref Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange by Michel Ciment).

Kearns suggests “The illusion [Kubrick] provides by use of art and design in A Clockwork Orange, emphasises the sterile dysfunction of this society by their characters not only adopting modern art but by violently throwing it in our faces”.

Later in the film we see the entrance to the Korova, whose black walls are covered with posters. One has a yellow background with green phallic-like nose which reminds us of Alex’s phallic mask and another is of a black woman with large afro which is much like two paintings seen in Dick’s bedroom either side of the TV in The Shining.

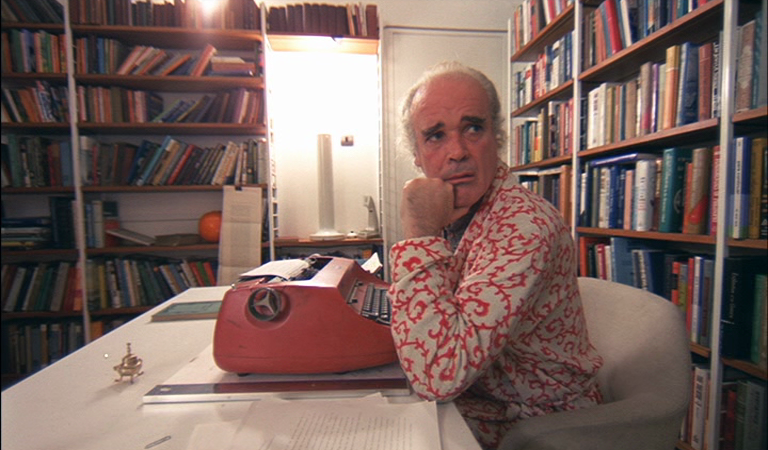

‘HOME’ – Mr and Mrs Alexander’s House

The exterior of ‘HOME’ is New House, Shipton-Under-Wychwood by Stout & Litchfield. The raked pebble garden was part modeled after the Ryoan-ji zen temple garden (Temple of the Dragon at Peace).

The interiors were shot somewhere else altogether – at Skybreak, Radlett, Hertfordshire – a home designed in 1965-1966 by a group of architects called Team 4. Within the four walls of this outstanding yet somewhat clinical architectural space, Alex and his Droogs reap havoc, attacking and paralysing Frank Alexander (Patrick Magee) and raping his wife (Adrienne Corri) all whilst Alex sings ‘Singin’ In The Rain’.

The writer Mr Alexander is found at home, typing away at a red IBM typewriter (N.B. Alex also has a red typewriter in his own bedroom we shall see later), a blue box to the side filled with typewritten paper and other stationery scatter the table. He sits in a Saarinen Executive/Conference chair and is flanked by a globe lamp on a pedestal and bookcases which house many books and, if you look carefully – an orange, circular object. In the book, the writer was working on A Clockwork Orange, a fact never revealed in the film.

The Saarinen Executive Armchair makes an appearance in the writer’s “Home” in A Clockwork Orange. Approx £1,125.00 Inclusive of VAT (eg UK) if applicable / $1768

Saarinen Executive Conference chair, with and without arms (new)

Designer: Eero Saarinen

Knoll

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Officially licensed Hicks’ Hexagon rugs and runners as seen in The Shining‘s Overlook Hotel (original design by David Hicks). High quality, custom made, hand tufted 1 ply wool. One of the most iconic carpets in film Approx £1,308.33 – £6,120.00 / $2056

Hicks’ Hexagon officially licensed luxury rugs and runners, designed by David Hicks, as seen in The Shining Overlook Hotel

Designer: David Hicks

Directors: Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, Mike Flanagan

Later Alex topples this table and we get a better look at the Saarinen chair:

The rest of this open plan house is divided by stairs and tiers of different heights, and displays carefully placed ultra modern, space-age 60s furniture, almost like a museum. The obsession with space age furniture was fuelled by the space race – we landed on the moon two years previous to A Clockwork Orange‘s release in 1969 and one year before 2001: A Space Odyssey.

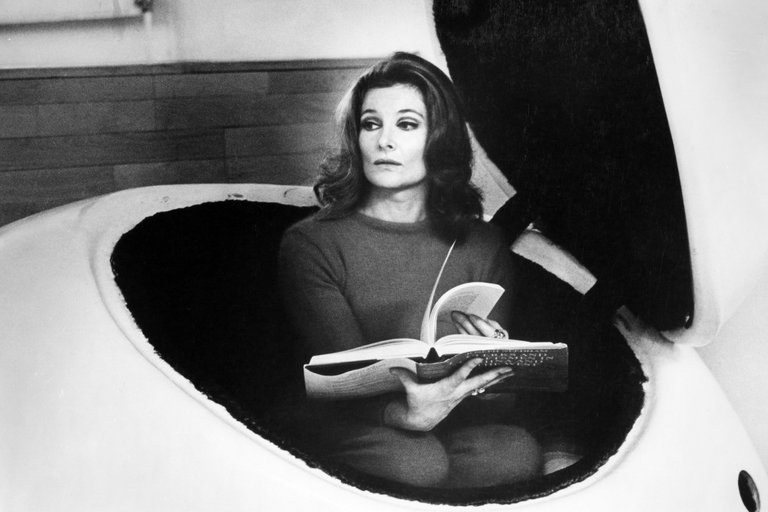

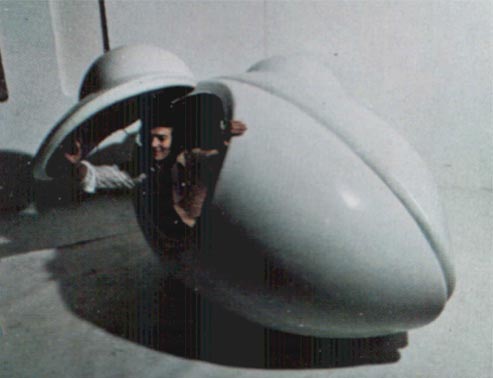

On the lower tier we find Mrs Alexander dressed from head to toe in red, sitting reading in a white pod with open ‘lid’ which forms a kind of heart shape. On the second tier we see a red and black low chair which also seems to form a heart. Together with the heart shaped art piece on the wall we could surmise (as did Juli Kearns) “HOME is where the heart is”.

The Alexander’s retreat pod is by Roger and Martin Dean who worked in many areas of design – from art, fantasy and science fiction books to appliances and architecture. Their designs are heavily inspired by Art Nouveau, though often with a very futuristic slant.

Kubrick did not choose his furniture pieces for mere aesthetics. The concept behind the pod as seen in A Clockwork Orange, echo themes in the story. The pod acted as a kind of dry floatation tank where, according to Martin Dean, “One can contrive to cut oneself off from the world. The Pod simulates conditions which are in some ways similar to brainwashing. Because the Pod is sound and light proof and has a soft fur interior to minimise touch, it disconnects you, and that’s a state in which you are most receptive to propaganda, or self-determined indoctrination via tape recorders, projectors, light effects, and so on. You could take your mind from a state of near sensory deprivation right through to sensory chaos.” This could almost be a description of the Ludovico treatment Alex undergoes later in the film.

“There is a guy called T. E. Hall who wrote a book on psychological space bubbles which people build up round themselves, and when they break they become neurotic. The Pod recreates this kind of bubble only in solid physical form,” continues Martin Dean.

The Retreat Pod was very much more than your average piece of furniture and the intention was like certain drugs, to induce self-awareness. In fact, Martin Dean believed there was a chance it could very well make drugs redundant. Awareness between people also increases inside the Pod: “There’s no point in telling lies to each other, all you have got is two lives, and any other social facades or barriers are meaningless.”

The Deans were part of a small number of designers and architects of the time with a good understanding of materials and technology. Roger Dean also designed many outstanding logos, stage sets and album covers including Yes and Asia – which throws up yet another connection for me as I would copy the Asia album cover over and over when I was a teenager. This process influenced me to become a graphic designer and go on to design hundreds of record sleeves and music campaigns.

Mrs Alexander gets up from her Retreat Pod to answer the door to Alex in a hallway flanked by mirrors which repeat the chequered flooring (Kubrick was a chess-obsessive). As they enter back into the main living space we see a row of huge light bulbs which echo the exposed light bulbs we saw earlier in the Korova bar and give the impression of a stage set where a theatrical performance will take place.

And oh, what a performance we are subjected to – ‘a real horrorshow’ as Alex and his Droogs attack Mr and Mrs Alexander.

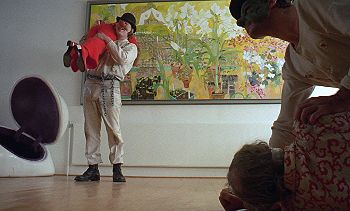

When Alex visits for the second time later in the film, HOME contains a glass and tubular steel dining table and set of chairs.

The dining tale and chairs make a fine backdrop for his meal of spaghetti and red wine, and could well be part of the ‘Locus Solus’ group designed by Gae Aulenti, or possibly designs by Giotto Stoppino or Gastone Rinaldi.

The large (5′ x 10ft) painting on the wall of a tranquil garden is by Kubrick’s wife Christiane, titled “Seedbox”. A similar painting also by Christiane Kubrick is seen in Eyes Wide Shut.

Alex tells us in his narration: “Where I lived was with my Dada and Mum in municipal flat block 18-A Linear North”. The exterior was in fact the Tavy Bridge Centre in Thamesmead.

The interior was created on the top floor of Canterbury House tower block, Borehamwood, Hertfordshire and is the epitome of post modernist 70s kitsch. The decor reeks of Alex’s middle-aged, working class parents trying to keep up with trends but lacking any real taste. It’s another horror show but incredibly captivating.

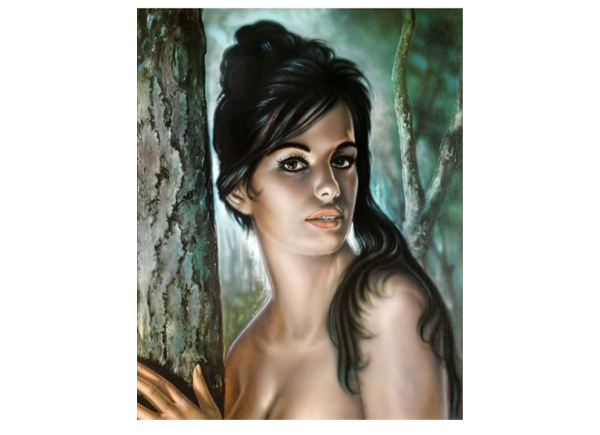

We see lurid gold wallpaper in the hall, loud graphic patterned wallpaper of various designs, a teal-coloured dogs tooth patterned sofa and chair, bulbous chrome-cladded walls, saturated colours and several JH Lynch paintings (‘Autumn Leaves’ ‘Nymph’ and ‘Tina’ were all highly popular mainstream art of the day). There is no respite for the senses here.

The first view we see of Alex’s home is the bathroom with gaudy diamond print orange, yellow and mirrored wallpaper which no doubt reflects every action including Alex taking a pee – the viewer becoming an unintentional voyeur. Even this would have been shocking for the 1971 audience.

The small kitchen is wallpapered with yellow, orange-red and mirrored metallic squares, and a toy sunflower cheerily smiles on the table.

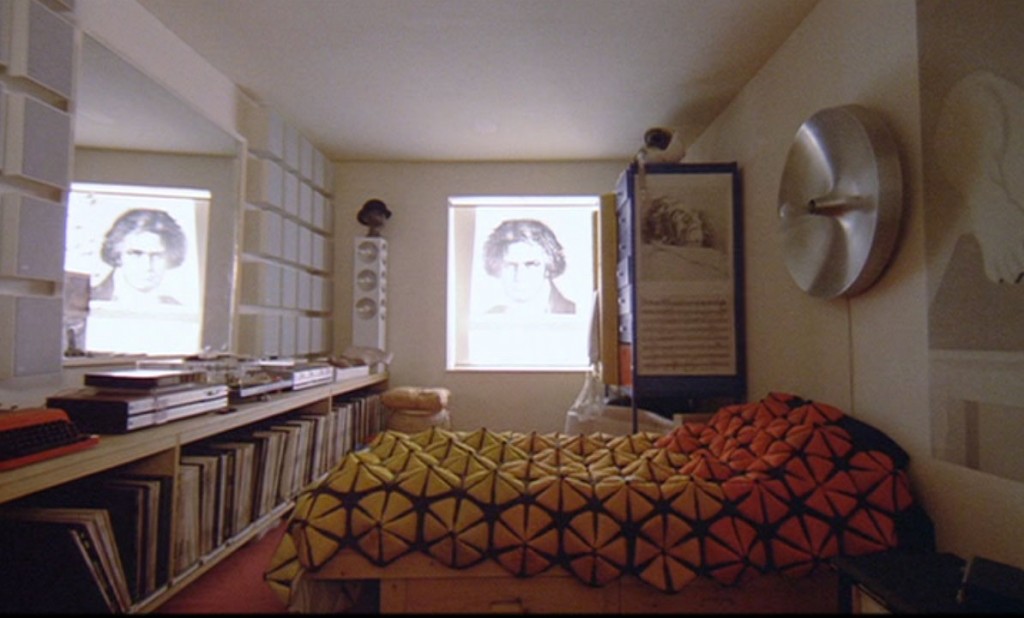

Alex’s own bedroom is a more sophisticated affair which bears more in common with HOME and presents a distinct contrast to the rest of the Alex’s parents flat. Here is where Alex spells out his individuality. Predominantly white, with large mirrors we see an orange and yellow bed spread with protruding cones or spikes (more on that here) on which an orgy is played at high-speed. The acceleration of the footage and the spikes in the quilt add to the representation of sexual brutality.

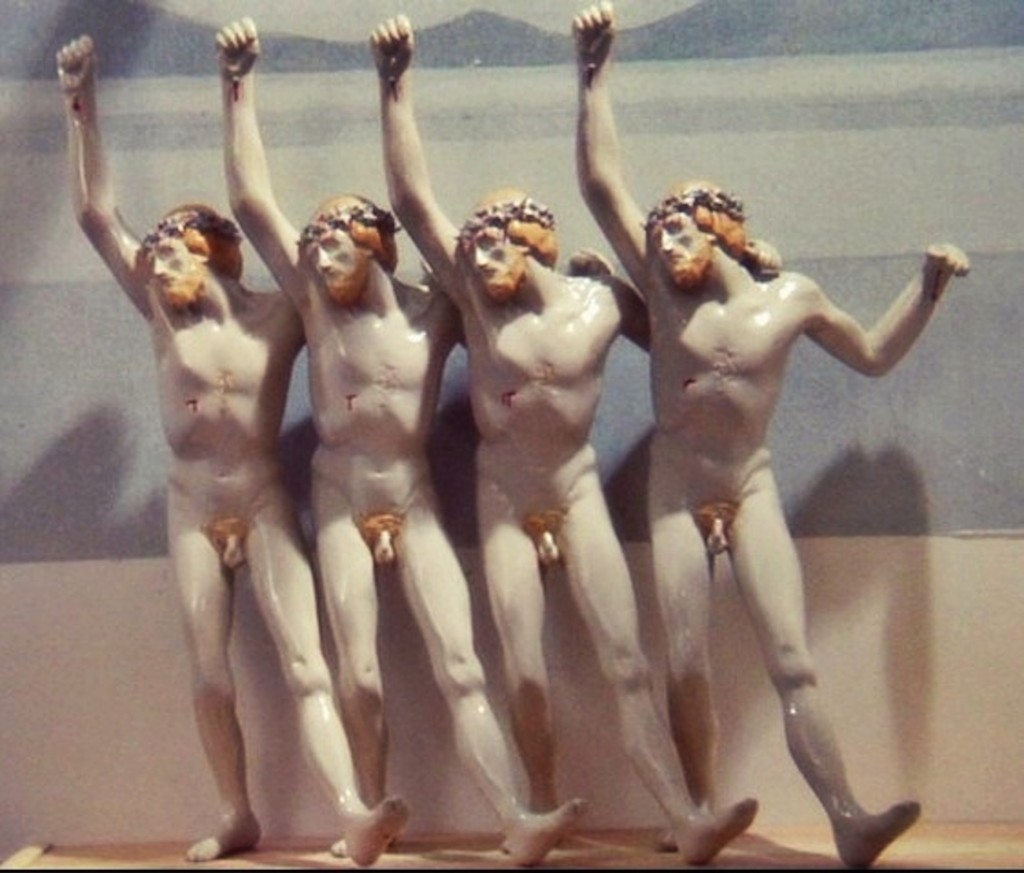

The mirror affords us another view of his single bed above which, hangs a large chrome globe wall sconce with exposed bulb and a graphic poster by Cornelius Makkink of a naked woman lying back with legs open. The branch on the wall (a perch for his pet snake) protrudes towards her vagina and a sculpture of four dancing Christ’s sits on the bedside table. This group of objects create a sort of biblical diarama of the temptation in the Garden of Eden which leads to the fall of humankind.

Christ Unlimited, the sculpture of four dancing Christs with exposed penises (presumably to echo the four droogs) which sits on Alex’s bedside table is by Cornelius Makkink’s brother Herman Makkink. These sculptures were originally made in 1970 in an edition 9 and it was the dancing Christs from this edition which were acquired by Kubrick for A Clockwork Orange.

A set of two Christ Unlimited sculptures from the original 1970 edition were sold by Christies in 2014 for £7,500 (numbered 6 and 8 in red paint at the underside of each right foot, each sized at 20 1/2 x 9 1/2 x 8 in. (52.1 x 24.1 x 20.3 cm). These Christies auction pieces were sold be vendors’ mother who purchased numbers 6 and 8 from the artist in the 1970s.

Christies’ website tells us “Herman Makkink and his brother Cornelis shared a studio at the S.P.A.C.E. complex at St. Katherine’s docks in London. In 1969 Stanley Kubrick visited S.P.A.C.E. to get ideas for the set design of his upcoming production A Clockwork Orange, eventually borrowing two sculpture works from Herman, Christ Unlimited and Rocking Machine, and nine paintings from Cornelis for use as props in the film. According to Herman, ‘… Christ Unlimited figures… formed part of my studio work at the time, and, after seeing them there, Kubrick wanted to use them for the film because they probably had the futuristic look he and his wife wanted. In the late sixties and early seventies, we, London based artists, felt terribly hip. We didn’t want to fight the establishment so much as shock them. Christ Unlimited was inspired by a crucified Christ statuette that I had found. The left arm and both legs from the waist down had been broken off. I replaced them in a more joyous pose – that of a dancer in the midst of a popular folk dance from the Balkans and the Middle East, known as The Butchers Dance”. Kubrick borrowed the full edition of nine dancing Christ’s for use in the film, though only four are seen in Alex’s bedroom. The full edition was returned to Herman Makkink after filming.

Some years later, the value of Christ Unlimited had increased significantly: A set of three 1970 editions numbered 1, 3 and 5 with an estimate of $8,000-$12,000 sold in a Phillips auction for $20,000

In 2005, Medicom Toy released an edition of 20-inch Christ Unlimited art toys sold in pairs of two. Three years later, the value of the figures had doubled, according to a Phillips de Pury 2008 auction. In 2009, another Japanese company, Nexus VII, released an even more limited all-black Christ Unlimited multiple.

We’ve had news that these sculptures may be rereleased in a new edition at some stage. We have our ear to the ground on this so please get in touch at [email protected] if you want to be notified when these are released, and also if you have any of the past editions of the Christ Unlimited sculptures to sell.

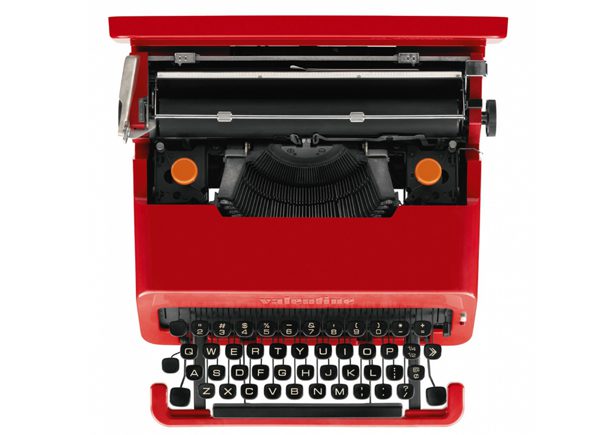

Alex is not the fourteen-year-old teen portrayed in Burgess’ book (Burgess, at the end of his book, blames Alex’s criminal behaviour on his just being a kid), in Kubrick’s film he is a young adult with mature tastes. On the long shelf we see a red Ettore Sottsass “Valentine” portable typewriter. This typewriter is one of the most famous examples of 1960s Italian design and bears witness to the time when Olivetti was leading the way in industrial design “the pre-digital precursor to the Macbook, as emblematic of style as it was of mobility”.

Designed by Ettore Sottsass and Perry A. King in 1969, the portable Valentine Olivetti typewriter is a design classic as seen in Alex’s bedroom in A Clockwork Orange Approx £236.67 Inclusive of VAT (eg UK) if applicable / $372

Valentine Olivetti Typewriter designed by Ettore Sottsass, portable, vintage

Designer: Ettore Sottsass

Olivetti

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Alex clearly has some money to afford such luxuries including the stereo system. A music lovers dream, the turntable on which Alex plays his beloved Beethoven records is the Transcriptors Hydraulic Reference Turntable (available to buy through Film and Furniture), a stunning award-winning piece first produced in the 60s. This turntable was designed and manufactured by David Gammon in 1964. The design was later licensed to J A Michell who made the turntables from 1973 to 1977. Gammon’s son Michael has told us “My father had a factory in Borehamwood and was approached by Stanley Kubrick and his production crew and supplied them with a turntable to use. He also gifted MoMa a turntable in 1969 where it still resides to this day.” More on the turntable here >.

This rare turntable has been displayed in various museums around the world including the Museum of Modern Art in New York which Michael Gammon refers to.

The multiple speakers on the wall are Braun L46 speakers designed by Dieter Rams. These Braun speakers were cleverly designed to integrate directly into the Vitsoe Universal shelving system and also has fixing points for wall-mounting in landscape or portrait position.

A large black and white image of Beethoven is printed on the window blind of Alex’s room. It moves as with the breeze as the music plays.

As Christian Anderson-Ramshall points out in an earlier guest feature for Film and Furniture: “Kubrick is renowned for his obsession with detail and his decoration of Alex’s bedroom not only amplifies his character, but acts as a counter point to his parents’ own tastes. His room serves not just as an act of rebellion, but the externalisation of his violent and lustful nature. Alex utilises his art and surroundings to express his own inner revulsion at society and a mirroring of his own brutality, but also as any young man – he just loves to be surrounded by cool stuff”.

It is the film set decoration and production design of these rooms which stick so strongly in my mind. The excess of loud, erotic, often obscene, art, sculptures and decor suggest that in the future we may become desensitised, which I believe both Burgess and Kubrick predicted with some degree of accuracy.

In Part 2 of this feature we investigate The Record Shop, CatLady’s House and The Ludovico Medical Facility. Read it here >

Film and Furniture founder Paula Benson will be talking with The Anthony Burgess Foundation at a screening of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) on Sunday 15th October (6.30pm, The Dancehouse, Manchester) as part of the Design Manchester 2017 Festival Film Season – Reframing Reality, co-curated by Christopher Frayling, Fiona McGarva and Malcolm Garrett.

Come along and join in the discussion.

Sunday 15th October, 6.30pm

The Dancehouse, Manchester

£10 (£8 Student with a valid NUS card)

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Instagram

Instagram Pinterest

Pinterest RSS

RSS